Introduction to the

Enneagram

It is one's psychological type which from the outset determines and limits a person's judgment.

Carl Jung

The Enneagram's deeper function is to point the way to who we are beyond the level of the personality, a dimension of ourselves that is infinitely more profound, more interesting, more rewarding, and more real.

Sandra Maitri

Mapping Our Journey Home

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time.

T. S. Elliot

The practice of mindfulness can often feel like a return home. We return home - fully - to the reality of what’s already actually happening, right now, and only now. We return to our body and heart and a basic sense of paying attention in all its beautiful simplicity and immediacy. It’s as if we were remembering and returning to when we were an infant, discovering something for the first time, in all its wonder. We let go of what our heavily conditioned mind is constantly trying to insist is happening, and we come home to the body and the heart and to naked awareness, just as it is, right here, right now. We open to what Buddhists prize as “beginner’s mind.” The Buddha once summarized his teaching as, “In what is seen is only what is seen. In what is heard is only what is heard. In what is sensed is only what is sensed.” The great Zen master Shunryu Suzuki stated the value of beginner’s mind quite simply: “In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities. In the expert’s mind, there are few.”

Yet, as T. S. Eliot says, and Dorothy learns in The Wizard of Oz, awakening to this wonderful simplicity of the now, paradoxically, requires a journey of some kind, even if it is finally discovering that it is a coming home to remembering what we somehow already know.

Discovering our Enneagram type is like this, an awakening to something we somehow always knew, but didn’t, at the same time.

Like a good treasure map, knowing our type points to the destination home - where “X marks the spot.” And, like a good map, once we learn to read it, it provides enough detail to help us find our way there. But, as I begin to arrive “home” to the reality of how I actually am, right here, right now - lo and behold! - “home” becomes merely a doorway into a whole new universe! What seemed ordinary and even, at first, painful and stuck, has suddenly become a doorway into a whole new realm of possibilities. Though I seem to have found my way home, a place I thought so familiar, I’m not actually just in Kansas anymore! Dorothy isn’t the same Dorothy at the end of The Wizard of Oz, and Kansas isn’t the same Kansas either.

There’s no place like home.

From The Wizard of Oz

The Enneagram

and the Law of Three

First she tasted the porridge of the Great Big Bear, and that was too hot for her. Next she tasted the porridge of the Middle-sized Bear, but that was too cold for her. And then she went to the porridge of the Little Wee Bear, and tasted it, and that was neither too hot nor too cold, but just right, and she liked it so well that she ate it all up, every bit!

From Goldilocks and the Three Bears (English Fairytale)

Why is the Enneagram such an especially powerful map of the way home? Much of its power is in how it helps us see into the core psychological makeup of the human psyche: the “three-foldness” of human nature.

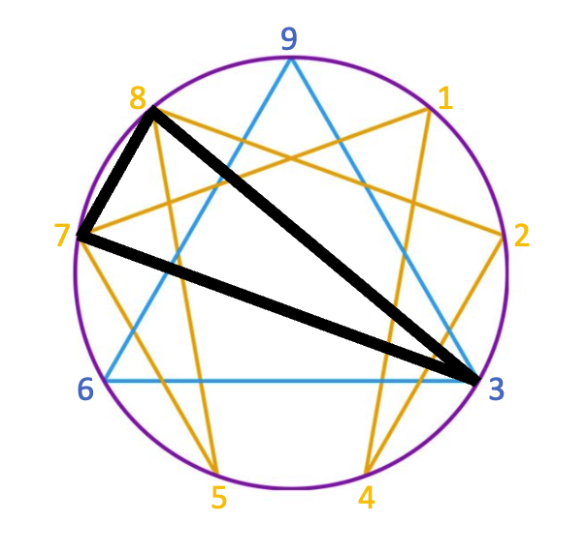

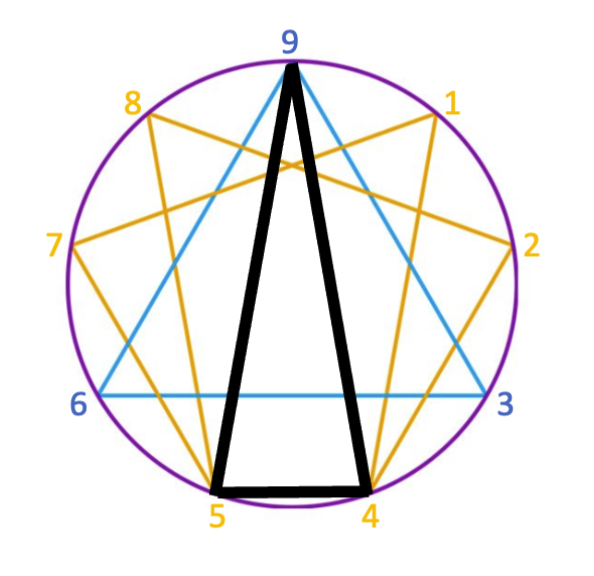

The Enneagram symbol is based on two simple numbers - three and seven - that are fundamental to many spiritual and religious traditions, and for understanding not only human nature but all kinds of phenomena. The number three is represented by the triangle shown in blue in the picture of the Enneagram above. This “three-foldness” is fundamental to understanding our deeper nature and working with the Enneagram.

George Gurdjieff is the first known person to work with the Enneagram symbol. Central to Gurdjieff’s psychology and cosmology - and the Enneagram - are what he calls the two fundamental “cosmic laws” based on these two numbers, the Law of Three and the Law of Seven. He describes the Law of Three as follows:

“We must examine the fundamental law that creates all phenomena in all the diversity or unity of all universes. This is the 'Law of Three' or the law of the three principles or the three forces. It consists of the fact that every phenomenon, on whatever scale and in whatever world it may take place, from molecular to cosmic phenomena, is the result of the combination or the meeting of three different and opposing forces . . . According to real, exact knowledge, one force, or two forces, can never produce a phenomenon. The presence of a third force is necessary, for it is only with the·help of a third force that the first two can produce what may be called a phenomenon, no matter in what sphere. The teaching of the three forces is at the root of all ancient systems. The first force may be called active or positive; the second, passive or negative; the third, neutralizing.” 5

Though this may seem abstract, an understanding of the Law of Three is immensely practical. When facing a conflict, for example, we may remember to ask ourselves “what is the third force that might resolve this?” Gurdjieff also refers to the three forces as “affirming, denying, and reconciling.” The two opposing affirming and denying forces in any conflict are obvious, but not so much this third “reconciling force.” Gurdjieff emphasizes that we are often “third force blind.” I have found that discerning this hidden - but critical - third reconciling force is an immensely valuable skill.

The power of “third force” is especially important in the practice of interpersonal mindful inquiry, a key mindfulness practice in using the Enneagram. Most often the inquiry occurs between two people (or between the person engaged in the inquiry and a group). The person who is inquiring - who is essentially meditating out loud - is seeking to maintain an inward creative balance between their “affirming” impulse and “denying” impulse. The affirming impulse is their conscious essential nature that wants to explore and inquire and have insight - and, ultimately, to awaken fully. The denying impulse is their fear-based conditioned personality that wants to continue as it always has, lost in thoughts and emotions, perhaps automatically doling out directions and judgments, “safely” unconscious of essence and its deeper capacities. The crucial, but subtle, third force is the other person (or group) who, in the “reconciling” role helps the inquirer to “hold the space,” so that both their essence and their personality can maintain a healthy dynamic dialogue of presence and discovery.

Three Centers of Intelligence

I would not be just a nothin’, my head all full of stuffin’, my heart all full of pain. I would dance and be merry, life would be a ding-a-derry, if I only had a brain.

……

When a man’s an empty kettle, he should be on his mettle, and yet I’m torn apart. Just because I’m presumin’ I could be kinda human if I only had a heart

.……

It's sad, believe me, Missy, when you're born to be a sissy, without the vim and verve. But I could change my habits, never more be scared of rabbits, if I only had the nerve.

The Scarecrow, Tinman, and Cowardly Lion from The Wizard of Oz

According to Gurdjieff the Law of Three is a crucial fact of basic human anatomy and psychology, and it not only sets humans apart from all other life on our planet but plays a pivotal role in the larger cosmos. Gurdjieff repeatedly emphasizes that we essentially have three “brains,” or centers of intelligence (something that modern biology and psychology also now recognize). These are the intellectual, emotional/feeling, and bodily/instinctual centers - he calls the latter the “moving” center. Crucial to our psychological and spiritual growth is the development of “three centered awareness” and the maturation of all three centers of intelligence in a balanced and integrated way. Gurdjieff calls his approach the “Fourth Way,” different from the other three spiritual “ways” that emphasize one of the centers over the others. Working with the Mindful Enneagram begins with this development of “three centered awareness” through the practice of mindfulness, with learning to remember to be present in all three centers of intelligence.

Gurdjieff refers to “man number one, man number two, and man number three” as three basic types of the initial, ordinary, undeveloped human being prior to a more advanced possible psychological evolution. He describes these three types as being based on the natural tendency from birth for each of us to lean more heavily on one of the three centers of intelligence.

Many people intuitively notice this tendency to naturally lean on one of the centers of intelligence, and it’s often reflected in stereotypical characters in fiction and movies. The “geek” is the “head type,” constantly trying to figure things out based on a vast compulsive accumulation of facts and using logic to a fault. The “bleeding heart” type always responds emotionally, is everyone’s best friend and is all too easily taken advantage of, or, conversely, the emotionally manipulative or smothering mother type. The “jock” can’t think or feel, but sure knows how to score points on the ball field. Beyond the stereotypes, most would recognize that some people, such as great athletes or musicians, are naturally gifted with an instinctive bodily capacity for creativity and skillful action. Others excel at intellectual pursuits, while still others are naturally “emotionally intelligent,” especially able to work with or manipulate others at an emotional level.

"Man number one, number two, and number three: these are people who constitute mechanical humanity on the same level on which they are born. Man number one means man in whom the center of gravity of his psychic life lies in the moving center. This is the man of the physical body, the man with whom the moving and the instinctive functions constantly outweigh the emotional and the thinking functions. Man number two means man on the same level of development, but man in whom the center of gravity of his psychic life lies in the emotional center, that is, man with whom the emotional functions outweigh all others; the man of feeling, the emotional man. Man number three means man on the same level of development but man in whom the center of gravity of his psychic life lies in the intellectual center, that is, man with whom the thinking functions gain the upper hand over the moving, instinctive, and emotional functions; the man of reason, who goes into everything from theories, from mental considerations. Every man is born number one, number two, or number three.” 6

Balancing Our Three “Intelligences”

Our reliance, starting from earliest infancy, on one of these three basic centers of Intelligence is at the core of why there are nine Enneagram types. These are:

Eight, Nine, and One: the “body types”

Two, Three, and Four the “heart types;”

Five, Six, and Seven the “head types.”

As Gurdjieff said, the path to awakening to our deeper essential (“Buddha”) nature and our deeper capacities must begin with seeing how this unconscious dependency on one center limits our psychological development. No one, of course, is actually a stereotypical “geek,” “bleeding heart,” or “jock.” We all have - and we all use - all three centers. But we almost always use them - unconsciously - in an unbalanced way that ultimately limits our happiness and effectiveness with family, friends, and colleagues, at work and at play.

The Enneagram can not only help us see this, but also points the way to a more harmonious and balanced way of using all of our centers of intelligence. Working mindfully and experientially with the Enneagram and the Law of Three helps us identify and work with our dominant center of intelligence - our internal “active force” - as well as our least developed and more reactive center - our internal “denying force.” And it will also help us work with our least visible or least valued center, which can become our “reconciling force” that enables all three centers of intelligence to work together more effectively.

We begin to learn the power of the Law of Three at the center of how we operate, which, for the most part, is unconscious, on auto-pilot. For types Five, Six, and Seven the automatically dominant center is the head, with the body or the heart as the underdeveloped or unrecognized center. Although, as we shall see, this imbalance unfolds in quite different ways for each of these three types. For types Eight, Nine, and One the body center, one’s “gut” sense, tends to dominate over the heart and the head - again, in different ways. For types Two, Three, and Four, it is the heart that predominates, one’s “emotional intelligence” (mostly unconsciously at first) and sense of relationship and connectedness with others.

As Gurdjieff teaches us, until all three centers of intelligence come online in our moment by moment awareness, we are more like machines rather than the kind of deeply sensitive, intelligent, and creative human beings possible for us. We are like a three legged stool missing two of its legs. We can never quite sit properly in who we fully are or are meant to be.

Three Temperaments

The Law of Three manifests in the Enneagram not only as an over-dependence on one of the three centers of intelligence - the head types, heart types, and body types - but also as three fundamental temperaments. The temperaments are three further variations on Gurdjieff’s three basic center-based types, and, hence, there are nine total Enneagram types.

Biological science recognizes that all creatures with even the most primitive nervous systems respond to threats in the environment - and, in humans, inwardly imagined threats - in one of three basic ways: fight, flight, or freeze. There are three equivalent psychological responses in humans as well. Just as we are predisposed from an early age to lean on one of the three centers of intelligence, we also favor one of three ways of responding to difficult situations. We see this as soon as infants begin to leave behind their initial normal narcissistic self-centeredness and realize they must contend with other people with needs that may conflict with their own. They become socially sensitive to relationships with other people and begin to develop the inward sense of a social self that must relate to different people in different ways.

Psychologist Karen Horney was the first to recognize three distinctly different typical tendencies in the ways that people respond to conflict and social stress and theorized how this begins at this early social stage of infant development. She noticed her patients typically responded by either “moving against,” “moving toward,” or “moving away” from the people with whom they feel in conflict. Later studies have demonstrated these three temperaments do manifest in infants at this very early social stage of development.

In the Enneagram, for each of the center-based (head, heart, and body) types, there are three further variations that reflect Horney’s three styles of adapting to conflict. Riso and Hudson call these the “Hornevian types:”

“The assertives (Horney's "moving against people”) include the Threes, Sevens, and Eights. The assertive types are ego-oriented and expansive. They respond to stress or difficulty by building up, reinforcing, or inflating their ego. They expand their ego in the face of difficulty rather than back down, withdraw, or seek protection from others. All three of these types have issues with processing their feelings.

“The compliants (Horney's "moving toward people") include types One, Two, and Six. These three types share a need to be of service to other people. They are the advocates, crusaders, public servants, and committed workers. All three respond to difficulty and stress by consulting with their superego to find out what is the right thing to do, asking themselves, "How can I meet the demands of what others expect of me? How can I be a responsible person?"

“The withdrawns (Horney's "moving away from people") include types Four, Five, and Nine. These types do not have much differentiation between their conscious self and their unconscious, unprocessed feelings, thoughts, and impulses. Their unconscious is always welling up into consciousness through daydreams and fantasies. All three types respond to stress by moving away from engagement with the world and into an "inner space" in their imagination.” 7

These three temperaments aren’t just limited to how we handle social conflict and relate to people. Our basic temperament of “moving against,” “moving toward,” and “moving away” also affects how we relate to the material world as well, such as our relationship with food or intoxicants, to physical pain or stimulation, with the natural world, and so on.

The Three Temperaments in Buddhism

The Buddha often speaks of the three core destructive human tendencies: greed, aversion, and delusion, what he calls the three “poisons” that underlie dukkha. The Buddha’s teaching about the Second Noble Truth: the cause of dukkha, unnecessary suffering, is “tanha,” fundamental thirst or craving. He said there are three forms of this fundamental craving at the root of dukkha, based on these three poisons. The first poison, greed, is the craving for sensual pleasure, constant stimulation, something we see is deeply embedded in our Western culture. Our capitalistic economic system is based on consumerism, aggressively driving us to a constant thirst for more and more. A second poison - delusion - is more subtle, but no less deeply embedded. It’s the craving for “existence,” for identity, to “be somebody.” Like Marlon Brando from the movie On the Waterfront: “I coulda had class. I coulda been a contender. I coulda been somebody. Instead of a bum, which is what I am.” It is the constant, mostly unconscious, quest to be what others want us to be, an established identity that is personality and ego-based rather than emerging moment by moment from essence and Buddha Nature. A third poison, hatred or aversion, is the craving for “non-existence.” This is the craving to avoid the unpleasant, to withdraw from conflict and difficulty and to seek safety over stimulation or identity. A later Buddhist master, Buddhaghosa, built upon this, articulating the three basic types of people who tend towards one of these three forms of fundamental craving: the “greed” types, “deluded” types, and the “aversive” types.

The “Assertive” Temperament

The “Withdrawn” Temperament

The assertive “greed” temperament seems clearly aligned with Horney’s “moving against” temperament. Think of the famous old beer commercial, “Grab for all the gusto you can!” Types Eight, Three, and Seven are constantly grasping for what they want, though quite differently, based on their dominant center of intelligence. Underdeveloped Eight’s - a body type - can be rather the bullies of the Enneagram, powering their way to grab what they want or think should happen, sometimes with little concern for others. Seven’s - a head type - are constantly grasping after the next exciting idea or experience, all to often ignoring what’s actually needed. Three’s - a heart type - are the “can do” folks of the Enneagram. They can’t help but heroically take on whatever image or outcome they intuit is desired or expected by whomever they happen to be with or whatever “tribe” they’re trying to impress. Although all three of these “moving against” types unconsciously lean on different centers of intelligence, the common denominator is ego inflation as their response to any kind of outward challenge, usually at the expense of their heart center.

What Buddhists would call the withdrawn “aversion” temperament is well aligned with Horney’s “moving away from” temperament. The core tendency of Fives, Nines, and Fours is to withdraw - mentally, physically, or emotionally. Fives - the head type with this temperament - withdraw into the intellect, observing from the safety of their considerable thinking machines and creating a safe distance between their largely unconscious inner sense of vulnerability and the scary world out there. Fours - the heart type - withdraw into intensely felt emotion, often unconsciously indulging in a deeply felt sense of their own tragic specialness compared with almost everyone else, who often seem to be happier than they. Nines - the body type - are born with a deeply bodily felt - sometimes painful - sensitivity to themselves and others, so they learn at a very young age to unconsciously withdraw so completely from their bodily felt sense that they often also have little sense of their own needs and desires. The common denominator of these “moving away from” types is to be especially lost in their inner world, dominated by what Freud called the “Id”, i.e., whatever images, emotions, and sensations are arising from the unconscious, moment by moment.

The “Compliant” Temperament

An alignment between the Buddhist “deluded” temperament and Horney’s compliant “moving towards” temperament may not be so obvious at first. But think of the proverbial deer caught in the headlights, a “freeze” response to fear or potential conflict. This manifests in the compliant types - Ones, Sixes, and Twos - as a constant, immediate, and unconscious surrender to the “inner judge” - their internalized (introjected) parent. They automatically move toward their inner judge and comply with its assumption (or projection) of what the other party in the conflict needs or wants, whether or not the other party actually does need or want that. Ones - as body types - can be the most obvious in this way, with an often intense, though unconscious, bodily felt urge to obey the inner judge’s absolute certainty about what is right versus wrong, good versus bad, beautiful versus ugly, and so on. Some Ones might project that automatic bodily need to assert this “correctness” inwardly against themselves. Others might project this need to assert the imperative for correctness outwardly upon others. Sixes - as head types - tend to focus unconsciously on obeying their inner judge’s authority, the inner judge as the all knowing parental figure. Like Ones, this can also be projected inward - not trusting their own genuine sense of authority in the face of their absolute inner parent/judge - or outward, constantly seeking, and feeling let down by, external authority figures. The inner judge of type Twos - as heart types - compels them to automatically meet the needs of others and even - without realizing it - taking great pride in their ability to meet those needs. Expressed more inwardly, some Twos project their inner judge onto others they deem able to meet the Two’s needs, rather than the other way around. With all the compliant types, the common denominator is this complete automatic surrender to the inner judge, what Freud called the “superego,” whether that is projected onto others or within. The “delusion” - in the Buddhist sense - is that one’s inner judge is who I really am, real and all powerful or all knowing, and cannot be denied, a powerful - and often powerfully wrong and painful - belief in the false sense of a “self.”

Why are there Nine Types?

As with the three centers of intelligence, we all share and respond with all three temperaments, yet with a tendency, from infancy, to lean more heavily on one of the three particular ways of responding. All three of these temperaments, our particular way that we tend to automatically respond to difficulty, multiplied by the three ways we unconsciously depend on one of three centers of intelligence, equals the nine types of the Enneagram. Knowing one’s Enneagram type - one’s dominant “intelligence” plus one’s dominant way of responding - shines a powerful light on the particular way each of us responds to ourselves and to the situations in our lives that is so automatic that we cannot see it otherwise. Guided by this map of the nine types of the Enneagram we begin to see how imbalanced our inner capacities are. We start to see how we fail to draw on the full capacities of all three of our “brains.” We begin to see the many ways we unconsciously fail to tap our full potential by getting in our own way through the unconscious conditioning of dukkha, our proclivity for greed, aversion, or delusion. Only then does it become clear how we can stop getting in our own way, free ourselves from dukkha, and operate on all cylinders in a balanced way.

Three Instincts

There is yet a third manifestation of the Law of Three in working with the Enneagram, a third way we are predisposed to think, feel, and behave, from birth and/or based on our early psychological environment. As Freud, Gurdjieff, and many others never cease to emphasize, we humans, apart from our capacity for intelligence, are nevertheless animals too, with instincts we share with our fellow living creatures. If we don’t develop a healthy relationship with our animal nature and its needs our animal nature will most certainly find unconscious ways of getting its needs met nevertheless.

Oscar Ichazo and Claudio Naranjo, who pioneered using the Enneagram to identify the nine basic personality types, also identified three basic sets of instincts that deeply affect how our type actually manifests. These are the instincts for self-preservation, sexuality, and adaptation or social connectedness. As with the three centers of intelligence and the three temperaments, some combination of these three sets of instincts tend to dominate our awareness from an early age in a particular way.

All humans, and all animals, are often preoccupied with self-preservation and with procreation and, at least with mammals, the need to adapt to one’s environment and be part of a family or tribe. Our instinctual “animal” nature must be taken into account when we are seeking deeper self-understanding and to be open to our deepest potential.

From a Buddhist or Enneagram perspective, it’s not that our animal instincts are “bad” or “wrong.” Indeed, our instincts may well save our life or make us feel fully alert, alive, vital, safe, protected, and appreciated. But our capacity for deeper development must include seeing and working with our unconscious tendency to be dominated by - or ignore - our instinctual drives. By awakening and developing our capacity for mindfulness we can greet and respond, rather than simply react to, the arising of these powerful instincts, in the immediacy of the present moment. Over time we can shift our relationship with our instincts and find a more healthy way of sensing what they need to tell us as well as satisfying their genuine needs.

There is a wolf in me . . . fangs pointed for tearing gashes . . . a red tongue for raw meat . . . and the hot lapping of blood—I keep this wolf because the wilderness gave it to me and the wilderness will not let it go.

There is a fox in me . . . a silver-gray fox . . . I sniff and guess . . . I pick things out of the wind and air . . . I nose in the dark night and take sleepers and eat them and hide the feathers . . . I circle and loop and double-cross.

There is a hog in me . . . a snout and a belly . . . a machinery for eating and grunting . . . a machinery for sleeping satisfied in the sun—I got this too from the wilderness and the wilderness will not let it go.

From “Wilderness” by Carl Sandburg

Each Type Has an Instinctual Flavor

Our relationship to these three basic sets of instincts strongly flavors how our Enneagram type shows up as we go about our daily life. In fact, people are often mistyped from not taking one’s instinctual orientation into account.

Like with the three centers of Intelligence and temperaments, we all, of course, have all three sets of instincts. We all have an instinct for self-preservation, for a sense of belonging, and not only a basic sex drive and desire for intimacy but also to be creative and seen and appreciated and to make a mark in the world. However, just like the centers, one of the three instincts tends to predominate, to be our “first line of defense,” our “affirming force” in the realm of animal instinct. At the same time, like with the centers, one of the other two instincts tends to be the more underdeveloped, repressed, “denying force” - to take a backseat to the dominant instinct. The remaining instinct is somewhere in the middle, the more hidden and unclear potentially “reconciling force.” A number of Enneagram teachers emphasize that uncovering and bringing to light the “repressed” instinct is the best place to start in working with the instincts. But the “middle” instinct is also potentially just as important, because it can be the “reconciling” and enabling instinctual relationship.

Our particular instinctual “stack” - whichever the three instincts are dominant, secondary, or repressed - is a critical “independent variable” in determining how our type manifests in a given situation. As we begin to explore each of the nine Enneagram types, we need to examine our particular overdependence on one type of intelligence and our temperament (our characteristic way of responding to difficulty) and how to come into balance with this. But we must also look at how our particular instinctual stack also shows up and flavors how we think, feel, and act.

For example, when we encounter a new situation or walk into a room, am I like a deer in the forest; do I immediately focus on potential danger or our personal safety (self-preservation instinct)? Or am I like a dog; do I tend to first sniff/scope out the people in the room and how they might perceive me or how I might need to relate to them (social instinct)? Or, like a lion, do I immediately see how it might be an opportunity to shine or dominate in some way (sexual instinct)?

Your Type’s Path of Development

Passions and Virtues - The language of the Enneagram does more than simply describe the threefold relationships of centers, temperaments and instincts for each of the nine types. It also provides a rich language for understanding the predominant reactive emotional climate - the “passion” - as well as the transformed sense of feeling for each type - the “virtue.” The virtue is the particular quality of feeling - the “higher emotion” - that each type must cultivate to move from their particular form of reactivity and dukkha - their particular passion - to a greater capacity to respond mindfully. This corresponds to what, in many spiritual traditions, is called the awakening of the heart - what Gurjieff called the “Higher Emotional Center.” With the Mindful Enneagram, we explore how the Second Foundation of Mindfulness - mindfulness of feeling (vedana) - is crucial to this awakening of the heart. But, in addition to working with mindfulness, we also work with the crucial “heartfulness” practices as well: cultivating the “Divine Abodes” (Brahma Viharas) of Loving Kindness, Compassion, Sympathetic Joy, and Equanimity. These Buddhist heartfulness practices can be used in particularly powerful ways to support the development of the particular virtues of each of the Enneagram types.

Holy Ideas - The Buddha’s Eightfold Path to awakening - the Fourth Noble Truth - begins with “Right View.” In the most basic sense, this has to do with having a working knowledge of Buddhist teachings, beginning with the Four Noble Truths. But, in Buddhism and with the Enneagram, the deeper process of awakening is also an opening to our capacity for wisdom (prajna) and insight (vipassana), what Gurdjieff calls the “Higher Intellectual Center.” As we awaken, our entire perspective transforms beyond the limited sense of a separate, vulnerable, embattled, ego-fixated self, towards the realization and living out of our essential non-dualistic “Buddha Nature.” The Buddha called this “anatta” - non-self. We begin to see and live from a non-dual, non-separate sense of ourselves that is at one with all of existence, moment by moment. We see that we are more like the entire ocean of shared consciousness, not merely the seemingly separate impermanent waves of consciousness that come and go. Each Enneagram type has, at its core, one or more “holy ideas” - enlightened views of non-dual existence and manifestation - that help to catalyze the opening of each type to its particular window on this Right View. With the Mindful Enneagram we work with the Holy Ideas - Right Views - particular to each type through the practices of the Third and Fourth Foundations of Mindfulness: mindfulness of mind states and mindfulness of the “dharmas” - enlightened views of the nature of the mind.

The Inner Lines: Each Type’s Developmental Path - Perhaps the most powerful aspect of the Enneagram is that it is not merely a map of our particular limitations, but, much more importantly, the particular deeper awakened capacities of our type and the path to develop those capacities. The inner lines of the Enneagram symbol point us to this developmental path. With the Mindful Enneagram we explore the inner lines for each type - how our predominant type is connected to the higher and lower qualities of two other connected types - and how this lays out our particular path to deep spiritual transformation.